– By GILDA V. BRYANT –

Update on TEXAS CATTLE FEVER TICKS

In the late 1800’s, Texas Cattle Fever caused extensive cattle losses. To combat this deadly disease caused by ticks, the Bureau of Animal Industries, predecessor of the USDA (see Looking Back, September/October 2017 issue, p. 162), developed the first tick eradication program in 1906. When ticks were controlled across the southeastern U.S., the USDA and Texas Animal Health Commission (TAHC) established a permanent quarantine zone along the Texas – Mexico border in 1943. Tick eradication was the preferred control method.

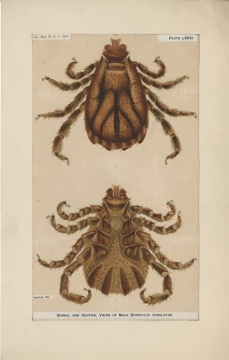

Two ticks, Rhipicephalus annulatus and R. microplus, can carry microscopic parasites, Babesia Bovis or B. bigemina, which cause Texas Cattle Fever. Sonja Swiger, Ph.D., Veterinary/Medical Extension Entomologist for Texas AgriLife A&M Extension, says the parasites enter the animal’s blood stream when parasite-infected ticks drink a blood meal. The parasites attack red blood cells, causing the animal to develop anemia, high fever and enlargement of the liver and spleen. It is fatal to some 90 percent of susceptible cattle. Although the protozoan is not in the U.S., they are active in Mexico and other countries.

“Our biggest concern is to not let the species reestablish itself because the more that appear, the more chances of the protozoan returning,” Swiger says. “In addition, these ticks can be so numerous on animals that they actually cause major health concerns from feeding. Even though we don’t have the protozoan now, it’s still not good to have ticks in such large numbers on a host.”

Cattle fever ticks are smaller than brown dog ticks and instead of living on several varieties of hosts, the fever tick spends its three life stages, larva, nymph and adult, on cattle and more recently, on wildlife. After females drink a blood meal, they drop to the ground to lay as many as 4,000 eggs. Eggs hatch into larvae, attaching to nearby cattle or deer, repeating the cycle. These ticks have unique, short mouthparts allowing USDA or TAHC inspectors to easily roll or scratch them out of the skin. These critters gather in soft tissue along the dewlap, brisket, forearm and flank. They also move slowly when removed, another way ranchers can identify them.

Protected by Quarantine

Texas quarantine zones are one tool used to control this pest. The Permanent Quarantine Zone runs 500 miles along the Texas — Mexico border, ranging from two hundred yards to 10 miles wide. The USDA Tick Force patrols this area, inspecting each animal. When ticks are found on livestock or wildlife, the property is designated as an “infected premises”, and placed under quarantine. If these ticks are discovered outside of the Permanent Quarantine Zone, that area becomes a Control Purpose Quarantine Area.

Tick control also includes gathering and treating cattle with scheduled dipping in Co-Ral every seven to 14 days for six to nine months under the supervision of a USDA or TAHC inspector.

The preferred treatment is injecting doramectin on a 25 to 28-day schedule for six to nine months, reducing the number of times cattle must be gathered. Horses are usually sprayed if ticks are found on them.

A third option starves ticks by removing cattle for nine months. This more economical approach begins by dipping cattle on a 7 to 14 day schedule. After two consecutive tick-free inspections, the herd moves to a new tick-free pasture.

Donald Thomas, Research Entomologist with the ARS Cattle Fever Tick Research Lab, says that USDA-APHIS pays for spray treatments, while the state of Texas pays for vaccines. Counties maintain dipping vats.

“The main cost to producers is the expense of gathering these animals,” Thomas explains. “Producers can receive a $5 per head, per roundup allowance from the Emergency Livestock Assistance Program (ELAP) available at their [county] Farm Service Agency [FSA] at the end of the year, if they keep track of how many times [animals were gathered] and the number of animals that were treated.”

Recently, Hurricane Harvey swept through coastal ranches. Thomas is confident the storm did not allow tick populations to increase or change quarantine zone boundaries.

Joe Paschal, Ph.D., Professor and Extension Livestock Specialist with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension, reports that the fever tick has adapted to feeding on deer.

“We’ve done a good job of increasing our deer population, providing better habitat and reducing parasites, like the screw worm,” Paschal says. “We’ve also introduced new species like the red deer, sika deer and an imported exotic antelope, the nilgai, in far south Texas. More ticks are being found on deer than on cattle.”

To control ticks in deer, the USDA and TAHC place ivermectin-treated corn in hog-proof feeders. Sixty days before hunting season, the corn is withdrawn until hunting season ends. Another control method is a four-post feeder. This elevated feeder has four foam-covered posts treated with permethrin. When deer eat the corn, the insecticide coats their neck and ears, killing ticks.

These two methods work well on deer; however the nilgai do not eat corn. Despite depopulation and fencing strategies, the nilgai have enlarged their territory, but are not the cause of ticks being found on a Live Oak County farm, 110 miles north of the Permanent Quarantine Zone in late 2016. Ticks have been seen on seven neighboring premises, causing the TAHC to set up a temporary Control Purpose Quarantine Zone requiring producers to begin tick treatments on their cattle.

“We need to be more observant of our animals, particularly ticks,” Paschal advises. “If you see something that doesn’t look familiar, pull it off [without mashing it]. Put it in a baggie or a medicine bottle. Call the TAHC at 512-832-6580 and they will direct you to a regional TAHC office and veterinarian.”

Mexico still has the fever tick and the protozoan that causes Texas Cattle Fever. The U.S. imports about a million head of stocker calves from Mexico annually. Paschal says those cattle must be tick free when crossing the border and if even one tick is found, the entire shipment is returned to Mexico. Some reports indicate that 50 percent of Mexican cattle have had Texas Cattle Tick fever, so they are carriers. These animals are transported to Texas Panhandle feedyards, which are inhospitable environments for ticks.

For more information, visit www.tahc.state.tx.us. To download the free tick app, go to: http://tickapp.tamu.edu.