By Marshall Cator

By Marshall Cator

The Kentucky Derby and all the hoopla of the “run for the roses” got me thinking about a story someone told me about visiting Secretariat’s grave. He described a fenced-off area along a little back road, tucked into a meadow, like so many little family cemeteries established long ago. It was isolated and peaceful, and the sun hadn’t been up long. On top of Secretariat’s headstone lay one single, fresh, perfect, long-stemmed red rose, with one perfect drop of dew shining in the early light.

A few weeks ago, I shared that story with a cowboy friend who then told me that he had been to Three Bars’ grave. Three Bars is as important to our cowboy horses as Secretariat is to the sport of kings. From what I’d read, though, it didn’t seem logical for Three Bars to be where the cowboy said he’d seen the grave. I asked if he thought he could find it again. The more we talked and “Googled,” the more important it seemed. Road trip tomorrow! Then I went to my personal library, and discovered a lot more to Three Bars’ story than I’d ever known.

The early years

Like Secretariat, Three Bars was foaled in Bourbon County, Kentucky. He arrived about a month after The American Quarter Horse Association was also “born” in 1940. In the future, when the AQHA faced a long, contentious rift about allowing horses with one Thoroughbred parent into the permanent registry, Three Bars and his offspring would ultimately help settle the debate.

His maternal grandsire won the 1914 Belmont Stakes. His dam, Myrtle Dee, set a track record for 5 1/2 furlongs at a track in Cincinnati. When Three Bars started race training, he was the standard by which the other colts were gauged, especially out of the gate. But he developed a strange problem. Whenever he really turned it on, he would come back to the barn with the muscle of his hind leg restricted and the flesh feeling cold, as if the circulation was cut off. They took him to Keeneland in Lexington and Detroit, but never raced him because of the mystery leg problem. Long story short, he was sold for $300.

Traded again, he ended up with a track blacksmith. Unraced at two, he was started only once at three, at Churchill Downs. But he won that race, and then was traded to a well-know show horse and harness man.

In 1944, Three Bars was sent to Detroit, where his mom had set a track record, and he won two of three races there. Somewhere along the way, his mysterious hind leg problem cleared up after he was treated for bloodworms, which a vet suspected of compromising his circulation.

That last race at Detroit was a six-furlong, $2,000 claiming race, and, along with winning by six lengths, he was “claimed” on behalf of two partners looking for horses to ship to back to Arizona.

Three Bars goes west, where he belongs

Arizona was then the mecca of “short horse racing.” That term means the races are shorter than a traditional Thoroughbred race – although the horses are typically shorter, too. (You probably know that’s where “Quarter Horse” came from: fastest horse at a quarter-mile.)

Delighting his new owners, Three Bars won a 3/8th-mile sprint at Albuquerque. But before he could prove himself again, racing was effectively cancelled. World War II and the resulting gas rationing changed everything. Gas wasn’t really in short supply, but Japan had cut off the U.S. rubber supply; there would be no more tires until who-knew-when.

During this layoff, in 1945, a rancher named Sid Vail caught his first sight of Three Bars. Then 32, Vail had fled his Mississippi childhood home at age 14 to become a cowboy. He now was ranching on his own near Douglas, Ariz., on the Mexican border. Vail was totally smitten by Three Bars. He offered $5,000 for him right away, then upped it to $10,000 (reading between the lines, a major financial sacrifice). The bid was accepted with the stipulation that if Three Bars was sound enough the sellers would get to race him in the future.

The next year, 1946, the six-year-old stallion raced a full season with 17 starts. He won eight, was second in three. A photo in an old Horseman magazine shows him way, way out in front in a five-furlong race in Phoenix, and the cutline says he set a track record. He won one stakes race, in Mexico. But by seven, he was no longer winning and retired permanently.

Vail was not yet established as a horseman, and had no facilities, so Three Bars stood at other people’s places with very little fanfare. Three Bars officially turned 10 on Jan. 1, 1950, having sired one Register of Merit Quarter racehorse. Soon, though, at a cafe in Tucson, a change in fortune was slowly set in motion. Vail was probably two hours away tending his ranch.

An Oklahoma horseman was eating breakfast and talking horses with a border patrolman he knew. He mentioned he was looking for a Thoroughbred stallion. The horseman, Walter Merrick, was sort of a cowboy-cross between John Wayne — tall, deliberate and handsome — and stockbroker E. F. Hutton. Merrick didn’t talk much, but when he did, people listened. He was only a couple of years older than Vail, but he’d proven the stallions Midnight Jr. and Grey Badger II, and raised and raced a slew of fast horses.

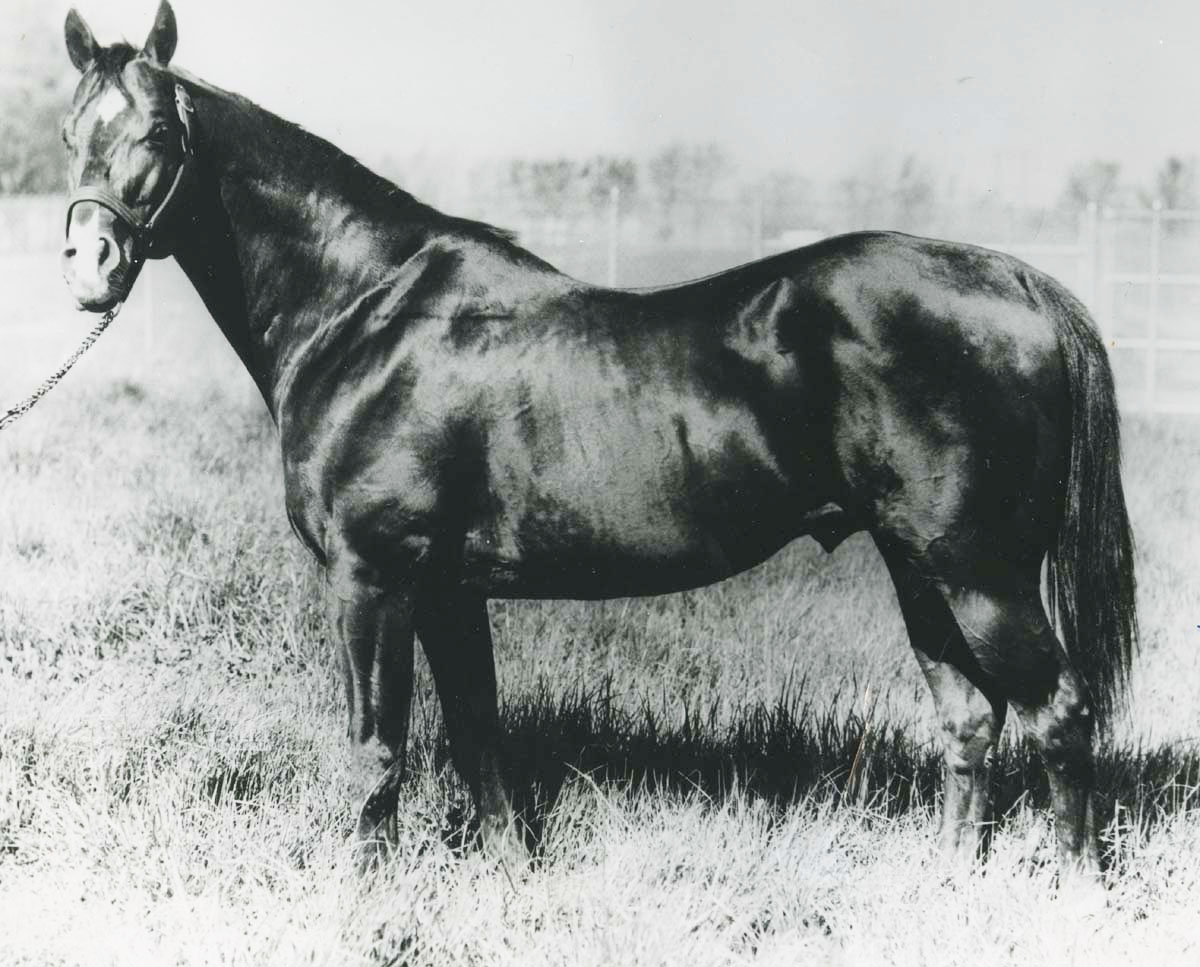

The patrolman drove Merrick eight miles south of Tucson where Vail was boarding Three Bars. Merrick said when he saw the sorrel gelding standing in the corral, he thought he was one of the best looking studs he had ever seen. He had a beautiful head, much better than Merrick expected from a Thoroughbred, and a big, intelligent eye. He was beautifully balanced and had a lot of muscle for his breed, but not short, bunchy muscle like a bulldog-type Quarter Horse.

Merrick called Vail at the ranch, ready to make a deal, but Vail wasn’t interested. He offered to stand the horse in Oklahoma, but Vail said no. Merrick admitted later he was heartsick to leave Arizona without Three Bars, and he asked Vail to call if he changed his mind. By the next season, the Three Bars-sired horses already running were getting more attention. His son Barred was featured as the horse of the month in the April 1951 Quarter Horse Journal. Still, it’s said the old horse only attracted 12-15.

Wisely, Vail called Merrick about his offer to stand Three Bars back in Oklahoma. Vail wanted to send his own mares to breed, too, of course. Merrick said he’d breed the same number of mares that Vail did and then charge a stud fee of $300 for outside mares, which they would split.

So in the spring of 1952, Merrick and Vail each bred 10 mares to Three Bars, plus an additional 50 outside mares. Many of the mares had more impressive records than the stud. Merrick’s endorsement went a long way.

Things were going so well, in fact, Vail decided he wanted to stand Three Bars again, although Merrick understood they had a two-year deal. Caught off-guard but not wanting to lose Three Bars, Merrick offered Vail $50,000. As Merrick silently did mental gymnastics for a way to get $50,000, Vail hesitated, but then loaded Three Bars up anyway.

That season, and those great mares, catapulted Three Bars’ reputation and the rest, as they say, is history. The horse Vail bought for $10,000 in 1945 fetched that same amount for a single breeding from 1963-1966.

Three Bars found true love late in life when Vail bought a blind bay mare named Fairy Adams in 1962. The stud was happiest when she was around, distraught when she wasn’t, and they were together until his passing in 1968.

The pilgrimage

I looked up “Three Bars Grave” on my phone’s map app and found two results — both in Athens, Greece. Fortunately, my friend’s memory led us to the general area. Bulldog tenacity and a minor stroke of luck finally led us to the grave. The location will have to remain confidential, “to protect the innocent,” by which I mean the property’s current owners. Also, to hopefully protect the guilty – my trespassing partner and me. I can assure you it is not where Quarter Horse historians would expect.

A rose granite base holds a bronze plaque with THREE BARS in big letters. It lists his sire, dam, 1940-1968, and Mr. & Mrs. Sidney H. Vail beneath the quote, “He ran the course until his race was won.” And in small letters it says: “The Grand Progenitor of Quarter Horse Racing.” It’s a lofty title, but actually an understatement. Racing was just the beginning.

BOX / SIDEBAR (So people relate him to modern times)

Sid Vail was interested in racing and ranch horses, but Three Bars’ sons and daughters excelled at even more. For instance, among Merrick’s first Three Bars race prospects, Matlock Rose and B.F. Phillips spotted the black stallion Steel Bars, ultimately agreeing to the $10,000 asking price after he’d been shipped to Centennial Racetrack in Denver. Returned to Texas, Steel Bars was grand champion at Fort Worth, San Antonio, Houston and Dallas — like some kind of quadruple crown — and overall high-point AQHA stallion. Suddenly Three Bars was considered more than a racehorse.

Three Bars’ grandson Impressive is possibly the most famous halter horse ever. His grandson, Zippo Pine Bars, is revered among pleasure horse breeders. And his grandson Doc Bar — well, everybody knows Doc Bar.